Giovanni Antonio da Pesaro

(Pesaro c. 1415 - before 1478 Pesaro)

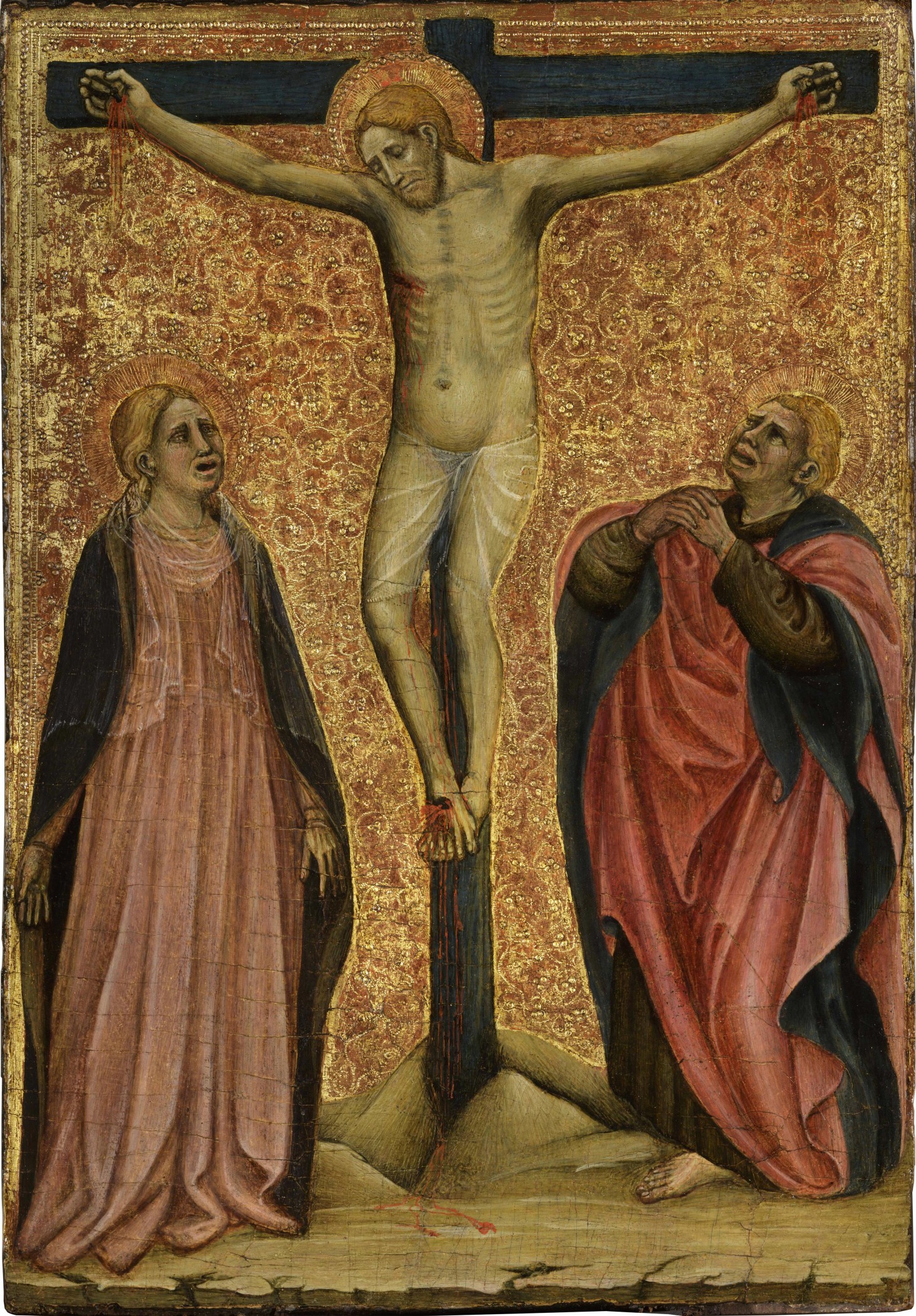

Crucifixion, c. 1440

tempera on panel, gold ground, 42 x 28,5 cm (16.54 x 11.22 inches)

Giovanni Antonio da Pesaro

(Pesaro c. 1415 - before 1478 Pesaro)

Crucifixion, c. 1440

tempera on panel, gold ground, 42 x 28,5 cm (16.54 x 11.22 inches)

Re: 740

Provenance: Alana collection, New York

Mostra Nazionale Antiquaria. Quattrocento pitture inedite, catalogo della mostra (Venezia, Procuratie Nuove), Venezia 1947, pp. X, 5, n. 15, tav. 1

Mostra della pittura bolognese del Trecento, catalogo della mostra (Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale), Bologna 1950, pp. 22, 35, n. 107

S. Bottari, C. Volpe, La pittura in Emilia nella prima metà del Quattrocento, dispensa al corso tenuto all’Università di Bologna nell’Anno Accademico 1957-58, Bologna 1958, p. 38

A. Porcella, in Mostra di antiche pitture e di scultura contemporanea, catalogo della mostra (Verbania, Teatro Sociale di Intra), Verbania 1960, pp. 27-29, 40

R. Longhi, Pittura bolognese ed emiliana del Trecento, in Id., Edizione delle opere complete, VI, Lavori in Valpadana dal Trecento al primo Cinquecento 1934-1964, Firenze 1973, p. 166

C. Volpe, La pittura nell'Emilia e nella Romagna. Raccolta di scritti sul Trecento e Quattrocento, a cura di D. Benati e L. Peruzzi, Modena 1993, pp. 69-70, fig. 124

A. De Marchi, Una tavola nella Narodna Galeria di Ljubljana e una proposta per Marco di Paolo Veneziano, in Gotika v Sloveniji. Nastajanje kulturnega prostora med Alpami, Panonijo in Jadranom, a cura di Janez Höfler, atti del convegno internazionale di studi (Ljubljana, Narodna Galerija, 20-22 ottobre 1994), Ljubljana 1995, pp. 249-251, nota 36

C. Guerzi, in Gentile da Fabriano e l’altro Rinascimento, a cura di L. Laureati e L. Mochi Onori, catalogo della mostra (Fabriano, Spedale di Santa Maria del Buon Gesù), Milano 2006, p. 106

M. Minardi, in The Alana Collection. Italian Paintings from the 14th to 16th Century, III, Firenze 2014, pp. 117-124, n. 17.

Federico Zeri Foundation n. 26245

Pictured at the time of his death, Christ is depicted with his eyes closed and his blood pouring copiously on his wounds; the weeping Virgin Mary and Saint John on his sides seem to cry out their pain, their mouths gaping and their features altered by sorrow. Below, a small ledge that lays the basis of the cross and its vertical axis, acts like the profile of the Golgotha.

This precious panel, remarkable in view of its perfect state of preservation, bears significant evidence of the transition from Late Gothic to early Renaissance in central Italy. The combination of elements conveying expressive realism, suggesting a medieval framework, and the plasticism of shapes – marking the transition towards a culture of perspective in the arts – has brought about the interest of first-rate collectors, in the last eighty years; furthermore, it has offered historians the chance to consider a work of this kind within its geographical provenance.

A pen note on the photo kept in the archive of the “Roberto Longhi” Foundation in Florence (inv. no. 0650140) indicates that the painting belonged to the dealer Vittorio Frascione in 1944, and Longhi himself was one of his chief consultants[i]. Three years later, it featured in the Antiques exhibition at the Procuratie Nuove Palace in Venice; Gino Calore and Giuseppe Fiocco carried out the expertise on that occasion and attributed the panel to an anonymous Tuscan master of the first half of the Quattrocento, marked by subtle references to Masaccio, as Alberto Riccoboni maintained in the introduction to the catalogue[ii]. Longhi held a substantially different view, for he had decided to insert the panel in the Mostra della pittura bolognese del ‘300 in 1950, an exhibition he had organised at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna; according to the historian, the painting was an early work by Giovanni da Modena, whose pitiful countenance was akin to the one in another Crucifixion, a panel kept in the Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia in Rome, as well as the famous Crossonce in San Francesco in Bologna (now at the Pinacoteca)[iii]. A few years later, Carlo Volpe drew attention to Longhi’s reasoning, thus maintaining the reference to Giovanni da Modena, but also identified the profiles of the figures bearing “an intellectual longing for archaic and neo-Giottoesque models, inconsistently darkened with a chiaroscuro sensitivity of a misinterpreted, decidedly more modern culture”[iv]. In essence, Volpe sensed a “bashful Renaissance” with hints from the Padana region, which would suggest dating the work around 1430 – hence consistent with the suggested attribution –, but it would also reveal Tuscan references that seldom appear in Giovanni’s production, itself modelled on the Gothic tradition of northern Italy. Albeit concisely, the historian consequently expressed doubts on the cultural heritage of the painting, suspended among traditions that are hard to reconcile. It remains a fact that the panel, in the meantime acquired by a Piedmontese collector, had been shown in the 1960 Antiques exhibition in Verbania bearing a reference to Jacopo Avanzi, another Emilian master, decidedly more consistent thanks to the re-evaluation of neo-Giottoesque plasticism, that Volpe had already identified in this work[v]. In 1995, within an essay dedicated to the Veneto painters of the second half of the Trecento in Istria, Andrea De Marchi put forward an attribution to Cristoforo Cortese, a Venice-based miniaturist showing several points of contact with the Paduan and Bolognese cultures[vi]. Miklòs Boskovits is to be thanked[vii]as he identified the correct reference to the figure of Giovanni Antonio Bellinzoni. Not surprisingly the son of a master who was born in Parma, he was another artist close to the Emilian tradition, who brought about the beginning of Renaissance in another territory, specifically in Pesaro, his native city, but overall in the northern Marche – some papers identify him working from Gradara as far as Cingoli, north of Macerata. Bearing this attribution, the work enters the prestigious Alana Collection in New York (Delaware), where it is published in a long article by Mauro Minardi[viii]. The son of Giliolo, Giovanni Antonio Bellinzoni was born around 1415 and started working, under the wings of his father, in the mid 1440s. The works carried out by both father and son, such as the first decorative campaign for the church of San Francesco in Pesaro (now Santa Maria delle Grazie) – a time when the fresco representing the Blessed Michelinakept in the sacristy –, but also the Three Saints, already part of the polyptych in the Parish Church of Gabicce Monte (Pesaro, Civic Museums) were executed, blatantly show a late Trecento approach, which has its roots in the culture of the Bolognese artists Jacopo Avanzi and Jacopo di Paolo, but also more broadly in the employment of a Giottoesque portrayal of forms, developed in the painting of the Padana region at end of the century[ix]. A fresco cycle in the church of San Francesco in Rovereto by Saltara (Pesaro-Urbino) epitomises a leap forward in the emancipation of Giovanni Antonio from the style of his father[x]: although the cycle can be ascribed to both painters, there emerges an unquestionable modernisation, most probably fashioned by the driving force of the young painter. It’s 1436 – as testified by the inscription at the foot of the last saint to the right – and Giovanni Antonio is a well-educated artist, aware of his skills. The similarities between the Crucifixion with Mourners, at the centre of the two Saintsgroup in the apse dome and our painting – none the less bearing the same subject – testify the accuracy of the reference suggested for our panel by Boskovitz, subsequently confirmed by Minardi and by now common knowledge.

The fluctuation between pertaining cultures, which emerges in the assessments of the historiography we have observed, is evident when formally observing this Crucifixion, poised between the linear nature stemming from Lombardy and the monumental composure of the figures, isolated by sharp contouring lines and a strong, sculptural chiaroscuro. Compared with the Saltara frescoes and the tablets depicting the Stories of Saint Blaisekept in the Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia collections and other private collections – a group reassembled by Federico Zeri, who ascribed it to the youthful output of Giovanni Antonio – this panel displays an expressive exploration that recalls contemporary experiences in Sienese painting, as well as an initial encounter between Giovanni Antonio and Bartolomeo di Tommaso – who was nonetheless active for the churches of Fano and Ancona. The turn of the decade is a pivotal moment in the career of our master, but also for the beginning of Renaissance painting in the Apennines in Italy. On the other hand, the refined use of the punch, the delicacy of tonal shades in the creases of the mourners’ red cloaks and the detailed rendering of the naturalistic details, blatantly suggest references to the models of Gentile and the International Gothic. This work, one of the most notable examples in the activity of a distinguished artist, epitomizes a tangible evidence of the encounter between parallel cultures, both alive and destined to coexist for at least a couple of decades in several areas of the Italian peninsula.

[i]The painting is in the envelope of Giovanni da Modena, although it is well-known that Longhi attributed it to Jacopo Avanzi, in a written note in 1946: see M. Minardi, in The Alana Collection. Italian Paintings from the 14th to 16th Century, III, Florence 2014, p. 123, note 4.

[ii]A. Riccoboni, in Mostra Nazionale Antiquaria. Quattrocento pitture inedite, exhibition catalogue (Venice, Procuratie Nuove), Venice 1947, p. X

[iii]R. Longhi, in Mostra della pittura bolognese del Trecento, exhibition catalogue (Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale), Bologna 1950, p. 22.

[iv]S. Bottari, C. Volpe, La pittura in Emilia nella prima metà del Quattrocento, from a paper for a course held at the University of Bologna in the Academic Year 1957-58, Bologna 1958, p. 38.

[v]A. Porcella, in Mostra di antiche pitture e di scultura contemporanea, exhibition catalogue (Verbania, Teatro Sociale di Intra), Verbania 1960, pp. 27-29.

[vi]A. De Marchi, Una tavola nella Narodna Galeria di Ljubljana e una proposta per Marco di Paolo Veneziano, in Gotika v Sloveniji. Nastajanje kulturnega prostora med Alpami, Panonijo in Jadranom, edited by Janez Höfler, proceedings of the International Conference of Studies (Ljubljana, Narodna Galerija, 20-22 October 1994), Ljubljana 1995, pp. 249-251, note 36.