Giovanni Fattori

(Leghorn, 1825 - Florence, 1908)

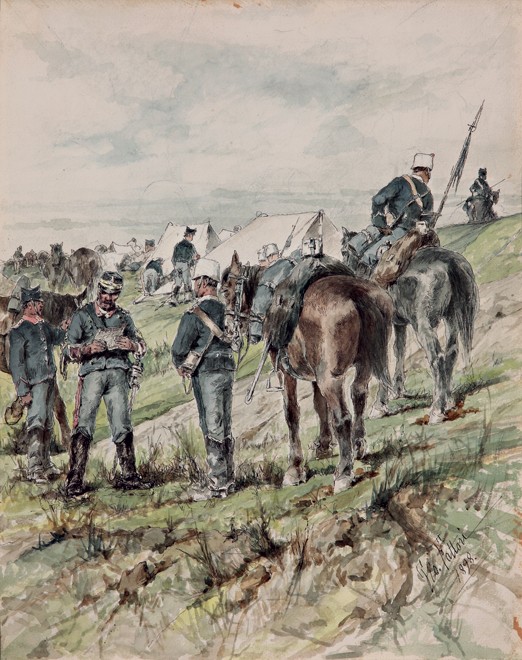

Napoleon III Receives a dispatch by Princess Eugenia near Lonato

Pen and brush, colored inks over traces of black chalk on paper;

465 x 369 mm (18.31 x 14.53 inches)

Giovanni Fattori

(Leghorn, 1825 - Florence, 1908)

Napoleon III Receives a dispatch by Princess Eugenia near Lonato

Pen and brush, colored inks over traces of black chalk on paper;

465 x 369 mm (18.31 x 14.53 inches)

Re: 0164

Provenance: Bernasconi collection, Mendrizio, Switzerland.

Price: Sold, or no longer available

Description:Emperor Napoleon III, wearing a French officerÂs uniform, is reading a letter brought him by a group of military couriers from Piedmont, recognisable from the allies thanks to the white headgear. The surrounding landscape has no distinctive characteristic, yet it is thought to be in the south-western area of Lake Garda, on the hills near Lonato, where the French army took over in June 1859, after MagentaÂs battle and the conquest of Lombardy.

The reconstruction of the scene in detail indicates that it is an important episode in the events development of the second war of Italian independence. What Napoleon III is reading full of concern is probably the dispatch arrived the 23rd of June from Paris, on which Empress Eugenia warned him of the need of ending hastily the military operations in Italy in order to bring back in France the army to protect the homeland from a probable Prussian aggression on the borders. It was this urgency that caused the combined French-Piedmontese attack on the next day against the Âquadrilateral resulting in the fierce battle of Solferino and San Martino, fundamental for winning the war. This amazing sheet is signed on the lower right part by Giovanni Fattori and is dated 1898. We are therefore looking at an historical commemoration, forty years later, of events already forming the ideological unity of the young nation. A character such as Napoleon III as well, whose person was unpopular amongst the Italian people due to his role in ending the 1849 Roman Republic experience and in preventing RomeÂs annexation to the Savoyard kingdom, is reassessed as protagonist of the Italian unification, the Risorgimento. Under King Umberto I, in fact, Italy was living that phenomenon that the historians (Ernest Gellner, Eric Hobsbawm) define as Âartificial nationalisationÂ, meaning the indoctrination of the popular classes through shared structures, such as mandatory elementary school education or the military service, with principles and founding myths of the unitary kingdom.

The fact that this sheet - maybe preparatory for a never made large canvas - is dated specifically 1898 is also significant because of these circumstances: two years earlier, the defeat at the battle of Adwa meant losing the Abyssinia war, resulting in national shame since for the first time the army of an European powerful state had been overwhelmed by the army of an African kingdom; the aftermaths of such a disaster were a substantial distrust of the Italian people towards the King and a weakening of the patriotic ideals. Aware of the danger, the Crown decided to establish on the 4th of March 1898 a national holiday for the celebration of the Albertine StatuteÂs fiftieth anniversary. It was an opportunity to underline the centrality of the KingÂs power during ItalyÂs unification. We can assume that our drawing was elaborated for this occasion1.

Giovanni Fattori had been the painting bard of the distressing heroism of the soldiers, tired after the success, the one who imprinted on his canvases first of all the struggle of carrying on the ideals of the love of oneÂs country2. By the end of the Century, just like Giuseppe Verdi, he represented the legacy of a far away and mythic time, told in teacher Perboni monthly stories on Cuore by Edmondo de Amicis. Therefore it does not come as a surprise that his style lost the directness of the 1860's paintings of (Carica di cavalleria a Montebello, Assalto alla Madonna della Scoperta), rather assuming a melancholic disposition. FattoriÂs Âhero-less Risorgimento of these years is fill with people featuring the same humaneness of the peasants of the Mercato di San Godenzo (Florence, Modern Art Gallery) or of the Butteri conduttori di mandrie (Livorno, Museo Civico Fattori)3,,almost as if soldiers and emperors carried out war not as a task they had chosen, but rather following the path of destiny. The landscape itself, vague on purpose, with the turfs made through few paintbrush traces, enhances this passage. The painter has no need in recording in detail the historicalevent,rathertranslatingitonthelyricalsphereand in this sense the preponderance of white in the chromatic choices increases the sensation of mirage, sunny chimera of a bright yet already elapsed future.

Therefore, the displayed drawing ideally closes an era. It is hardly surprising that many interpreters of ItalyÂs symbolism painting, from Pelizza to Segantini and Michetti, considered in these years the example of the tutelar deity of the previous season.

The reconstruction of the scene in detail indicates that it is an important episode in the events development of the second war of Italian independence. What Napoleon III is reading full of concern is probably the dispatch arrived the 23rd of June from Paris, on which Empress Eugenia warned him of the need of ending hastily the military operations in Italy in order to bring back in France the army to protect the homeland from a probable Prussian aggression on the borders. It was this urgency that caused the combined French-Piedmontese attack on the next day against the Âquadrilateral resulting in the fierce battle of Solferino and San Martino, fundamental for winning the war. This amazing sheet is signed on the lower right part by Giovanni Fattori and is dated 1898. We are therefore looking at an historical commemoration, forty years later, of events already forming the ideological unity of the young nation. A character such as Napoleon III as well, whose person was unpopular amongst the Italian people due to his role in ending the 1849 Roman Republic experience and in preventing RomeÂs annexation to the Savoyard kingdom, is reassessed as protagonist of the Italian unification, the Risorgimento. Under King Umberto I, in fact, Italy was living that phenomenon that the historians (Ernest Gellner, Eric Hobsbawm) define as Âartificial nationalisationÂ, meaning the indoctrination of the popular classes through shared structures, such as mandatory elementary school education or the military service, with principles and founding myths of the unitary kingdom.

The fact that this sheet - maybe preparatory for a never made large canvas - is dated specifically 1898 is also significant because of these circumstances: two years earlier, the defeat at the battle of Adwa meant losing the Abyssinia war, resulting in national shame since for the first time the army of an European powerful state had been overwhelmed by the army of an African kingdom; the aftermaths of such a disaster were a substantial distrust of the Italian people towards the King and a weakening of the patriotic ideals. Aware of the danger, the Crown decided to establish on the 4th of March 1898 a national holiday for the celebration of the Albertine StatuteÂs fiftieth anniversary. It was an opportunity to underline the centrality of the KingÂs power during ItalyÂs unification. We can assume that our drawing was elaborated for this occasion1.

Giovanni Fattori had been the painting bard of the distressing heroism of the soldiers, tired after the success, the one who imprinted on his canvases first of all the struggle of carrying on the ideals of the love of oneÂs country2. By the end of the Century, just like Giuseppe Verdi, he represented the legacy of a far away and mythic time, told in teacher Perboni monthly stories on Cuore by Edmondo de Amicis. Therefore it does not come as a surprise that his style lost the directness of the 1860's paintings of (Carica di cavalleria a Montebello, Assalto alla Madonna della Scoperta), rather assuming a melancholic disposition. FattoriÂs Âhero-less Risorgimento of these years is fill with people featuring the same humaneness of the peasants of the Mercato di San Godenzo (Florence, Modern Art Gallery) or of the Butteri conduttori di mandrie (Livorno, Museo Civico Fattori)3,,almost as if soldiers and emperors carried out war not as a task they had chosen, but rather following the path of destiny. The landscape itself, vague on purpose, with the turfs made through few paintbrush traces, enhances this passage. The painter has no need in recording in detail the historicalevent,rathertranslatingitonthelyricalsphereand in this sense the preponderance of white in the chromatic choices increases the sensation of mirage, sunny chimera of a bright yet already elapsed future.

Therefore, the displayed drawing ideally closes an era. It is hardly surprising that many interpreters of ItalyÂs symbolism painting, from Pelizza to Segantini and Michetti, considered in these years the example of the tutelar deity of the previous season.